Table of Contents

ToggleWhy Does Spicy Food Make You Cry? The Real Chemistry Explained

Ever bitten into a chili and suddenly your eyes start watering, your nose runs, and your mouth feels like it’s on fire? You reach for water, but somehow it makes things worse. The truth is, there’s real chemistry behind this reaction and knowing it can help you handle the burn smarter.

Quick Answer:

Spicy food makes you cry because molecules like capsaicin in chili peppers trick your heat-sensing nerves. These nerves normally react to actual heat (above ~42°C), but capsaicin binds to the same receptors and sends a false alarm to your brain. Your body treats it like danger and turns on the tear glands to flush out the “threat.”

Why Does Spicy Food Make You Cry – Chemistry Behind the Heat

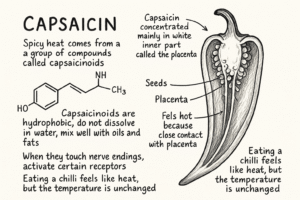

The “fire” in spicy food comes from a family of compounds called capsaicinoids, found only in chili peppers. The strongest and most abundant of these is capsaicin the molecule that makes your tongue burn and your eyes water.

Inside a chili, capsaicin isn’t spread evenly. Most of it hides in the white placenta the soft tissue that connects to the stem and holds the seeds in place. The thin white ribs running down the pepper walls also contain high amounts. The seeds themselves don’t make capsaicin, but because they’re coated by the placenta, they can feel just as fiery when you bite into them.

Capsaicinoids are hydrophobic they don’t dissolve in water. Instead, they mix with oils and fats. That’s why rinsing your mouth with water doesn’t help; it only spreads the burn. But when these molecules touch the nerve endings in your mouth, nose, or even eyes, they activate the same receptors that normally respond to real heat or injury. This is why a chili feels hot even though its temperature hasn’t changed

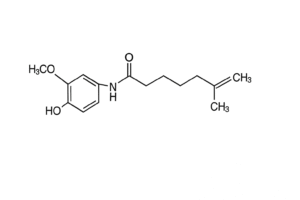

At the molecular level, capsaicin is a clever little chemical designed to trick your nerves. Its structure has three main parts:

-

Polar head (vanillyl group): This part helps capsaicin “dock” into heat-sensing proteins like the TRPV1 receptor.

-

Amide linkage: The connector that ties the molecule together.

-

Nonpolar tail (long hydrocarbon chain): This greasy tail makes capsaicin hydrophobic, so it doesn’t dissolve in water but mixes easily with oils, fats, and cell membranes.

Inside a chili pepper, capsaicin is mostly stored in tiny oil glands on the placenta (the white tissue inside the pepper). The flesh of the chili has much less, and the seeds don’t make capsaicin at all though they often feel hot because they’re coated with it.

How Capsaicin Triggers Heat Signals -TRPV1 Receptor Chemistry

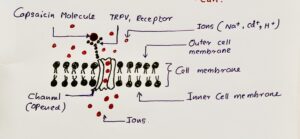

When you bite into a chili, capsaicin molecules travel through your saliva and reach the tiny nerve endings scattered across your tongue and mouth lining. These nerves are fitted with a special protein channel called the TRPV1 receptor (Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1).

What TRPV1 normally does:

-

TRPV1 is a heat and pain sensor.

-

Under natural conditions, it stays closed until it detects something dangerous like food or liquid hotter than ~42 °C, or physical irritation such as a burn or abrasion.

-

Once activated, it opens its channel, allowing positively charged ions like calcium (Ca²⁺) and sodium (Na⁺) to rush into the nerve cell.

-

This triggers an electrical impulse that shoots up the nerve pathway to your brain, which interprets it as “pain” or “burn.”

How capsaicin hijacks this system:

-

The polar vanillyl head of capsaicin fits perfectly into the receptor’s binding pocket, almost like a fake key in a lock.

-

By binding, capsaicin lowers the receptor’s activation threshold. This means TRPV1 opens even at normal body temperature.

-

Suddenly, ions flood into the nerve as if you’d just touched boiling water.

-

Your brain receives this message and reacts as though your mouth is literally on fire even though the food itself isn’t physically hot.

Other spicy molecules act the same way, but with different targets:

-

Piperine (black pepper) → also activates TRPV1, but more weakly.

-

Allyl isothiocyanate (mustard, horseradish, wasabi) → activates a related receptor called TRPA1, giving that sharp, nose-clearing sting.

-

Gingerol (ginger) → activates TRPV1 and related receptors, producing warmth rather than pain.

So, capsaicin doesn’t just cause a burning sensation it hacks your nervous system into sounding a false fire alarm. That’s why one small bite of chili can unleash the full cascade of tears, sweat, and runny nose.

Why Your Eyes Water – The Trigeminal Nerve Pathways Explained

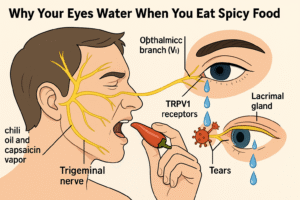

If spicy food only affected your mouth, it would already be intense enough. But often, just a few bites in, your eyes start watering uncontrollably. Why does this happen? The answer lies in the trigeminal nerve system, one of the most powerful sensory networks in your head.

How the irritation spreads to your eyes:

-

When you chew a chili, tiny droplets of chili oil and capsaicin vapor can rise up into the air.

-

Even microscopic amounts are enough to irritate the moist tissues around your eyes and nose.

-

These tissues are packed with branches of the trigeminal nerve, the same network that carries pain and heat signals from your mouth.

The trigeminal nerve in action:

-

The trigeminal nerve has three main branches: one for your forehead/eyes (ophthalmic), one for your cheeks/nose (maxillary), and one for your jaw/mouth (mandibular).

-

When capsaicin binds to TRPV1 receptors on these nerve endings near your eyes, it sends a powerful “irritant” signal to your brain.

-

Your brain interprets this as an emergency something potentially damaging is touching your eye.

Why tears start flowing:

-

To protect your vision, your brain commands the lacrimal glands (tear glands above each eye) to release fluid.

-

This tearing reflex is a chemical defense system: it dilutes and flushes out the irritant before it can cause real harm.

-

The result: watery eyes, blurred vision, and lots of blinking even though you never touched your eye directly.

Extra note:

This is also why cutting or frying chilies can sting your eyes even if you don’t touch them. The airborne capsaicin particles find their way to your trigeminal nerve endings around the eyes.

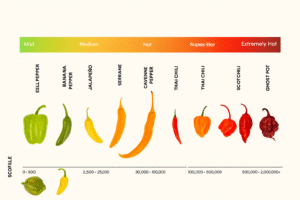

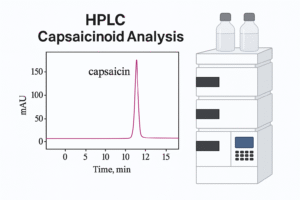

Measuring Heat – Scoville Scale vs HPLC Capsaicinoid Analysis

The “heat” of a pepper is not just a matter of taste it can be measured. Traditionally, pepper heat was rated using the Scoville Heat Scale, developed by Wilbur Scoville in 1912. In this method, a pepper extract is diluted in sugar water and given to a panel of tasters. The more dilution required before the heat is no longer detected, the higher the pepper’s Scoville Heat Units (SHU). For example, a mild bell pepper has 0 SHU, while a Carolina Reaper can exceed 2 million SHU.

While the Scoville method is historically important, it depends on human perception, which can vary between people and is influenced by fatigue during tasting. Modern food chemistry now uses High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to measure capsaicinoids directly. HPLC separates the compounds in a pepper extract, identifies each capsaicinoid, and calculates their exact concentration. These concentrations can then be converted into an equivalent Scoville rating for consistency.

HPLC offers much greater accuracy and repeatability, making it the preferred method for scientific research, food production, and quality control — though Scoville ratings remain popular for packaging and marketing because they are familiar to consumers.

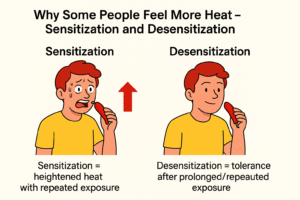

Why Some People Feel More Heat – Sensitization and Desensitization

Have you ever noticed how some people can bite into a hot chili and barely flinch, while others break into a sweat from just a sprinkle of pepper? That’s not just bravado there’s real science behind it.

The key lies in how your body responds to capsaicin, the active compound in chili peppers that creates that burning sensation. Capsaicin binds to special receptors in your nervous system called TRPV1 receptors, which normally respond to heat and physical irritation. When these receptors are activated, they send a message to your brain that says: “Hey, this is hot!”

Building Tolerance Over Time

When you’re new to spicy food, your TRPV1 receptors are very responsive. Even small amounts of capsaicin can feel intense. But if you keep eating spicy foods regularly, your nervous system starts to adapt. Over time, those receptors become less sensitive a process called desensitization. Fewer signals get sent to the brain, and the same chili that once made you tear up might now seem mild.

This is how chili lovers build tolerance not because they’re immune to pain, but because their sensory system adjusts to the repeated stimulation.

When Sensitization Happens Instead

On the flip side, if your receptors are overstimulated too quickly, they can actually become more sensitive a phenomenon called sensitization. This can happen if you eat a large amount of chili at once or consume several spicy meals in a short period. Suddenly, even a mild salsa can feel like fire.

Your Genetics Also Matter

Beyond exposure, your personal tolerance to spice may also be shaped by genetics. Some people naturally have more TRPV1 receptors or more sensitive nerve endings, while others inherit versions of the receptor that respond differently to capsaicin.

This mix of biology, experience, and even culture helps explain why spice tolerance varies so widely not just between people, but across entire cuisines.

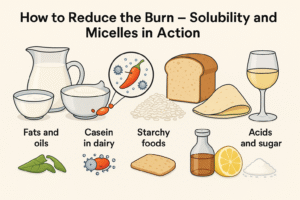

How to Reduce the Burn – Solubility and Micelles in Action

How to Reduce the Burn – Chemistry in Action

If you’ve ever tried to cool your mouth down with a glass of water after eating something spicy, you probably learned the hard way: it doesn’t help in fact, it can make things worse. But why?

The reason is simple chemistry: capsaicin, the active compound in chili peppers, is hydrophobic. That means it doesn’t dissolve in water, it actually repels it, much like oil does. So when you drink water, you’re not washing it away you’re just spreading it around, making the burning sensation feel even more intense.

What Does Work – The Science Behind Spice Relief:

Dairy: Fat + Protein Combo

Milk, yogurt, and cheese are some of the best options. Here’s why:

-

Fats in dairy can dissolve capsaicin and lift it off the nerve endings.

-

Casein, a protein found in dairy, works like a tiny sponge. It wraps around capsaicin molecules and helps carry them away when you swallow.

This is why whole milk or yogurt is more effective than skim milk , you get both fat and protein working together.

Starchy Foods: Absorb the Burn

Foods like bread, rice, or tortillas don’t chemically break down capsaicin, but they physically absorb it. This helps remove some of the compound from your mouth, reducing how much reaches your sensitive nerve endings.

Cooking Oils or Fats

Because capsaicin dissolves well in oil, even a small amount of oil or creamy sauces (like coconut milk or butter-based sauces) can help reduce the burn. These are especially helpful if you’ve eaten a dish with high levels of chili oil.

Acids & Citrus

Acidic ingredients like lemon juice or vinegar don’t remove capsaicin, but they can change the way your mouth perceives the burn. They tweak the pH environment in your mouth slightly, which may reduce how strongly your receptors react.

Alcohol: Not Practical, But Technically Effective

Capsaicin does dissolve in alcohol (ethanol), but most drinks don’t contain enough alcohol to make a difference. For relief, you’d need a very high-proof alcohol and that’s not exactly mealtime-friendly.

Sugar: A Distraction Tactic

Sugars don’t interact chemically with capsaicin, but they can distract your brain with a competing sensation. A spoonful of honey or a sweet drink may help take your mind off the pain — temporarily.

Bottom Line:

To actually neutralize capsaicin, go with fat-rich and protein-rich foods, especially dairy. Starches can help physically mop it up, while acidic or sugary ingredients offer temporary sensory relief. Water, sadly, only spreads the pain.

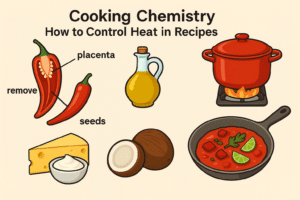

Cooking Chemistry – How to Control Heat in Recipes

Spice levels in food aren’t just about how hot a chili is they also depend on how you handle it in the kitchen. With a little knowledge of where capsaicin lives and how it behaves, you can take control of the heat in your dishes.

Where the Heat Lives

Capsaicin isn’t spread evenly throughout a chili pepper. The highest concentrations are found in the white parts inside the pepper the placenta (the pith that holds the seeds) and the ribs.

-

Pro tip: Removing these parts before cooking can reduce the heat significantly.

Fun fact: While the seeds themselves don’t produce capsaicin, they often feel hot because they’re coated with oils from the surrounding placenta.

Heat-Stable Means Long-Lasting

Capsaicin doesn’t break down during cooking. Whether you fry it, boil it, or bake it the heat stays.

-

Simmering or slow cooking won’t “mellow” the chili instead, it spreads the capsaicin evenly through the dish.

-

So the longer it cooks, the more widespread the burn becomes.

How to Tone It Down Even After Cooking

If a dish turns out hotter than expected, you still have options:

-

Add fat-rich ingredients like cream, cheese, or coconut milk. These help dissolve and dilute capsaicin.

-

Increase the amount of non-spicy bulk, like rice, potatoes, or other neutral foods to balance it out.

Strategic Cooking Tips

-

Add chili early in the cooking process if you want its flavor but plan to tone down the heat. You can later remove some of the oil or fat it was cooked in where much of the capsaicin has dissolved.

-

Pair chilies with acidic ingredients like lime juice, tomatoes, or vinegar to soften the perceived spiciness.

-

A touch of sweetness, such as honey or sugar, can also balance out the flavor and reduce how aggressive the spice feels even though the capsaicin level remains the same.

Final Takeaway:

Understanding the chemistry of capsaicin lets you dial spice up or down based on how you prep, cook, and balance your ingredients. The secret isn’t always more or less chili it’s how you treat it in the pan

Capsaicin vs. Dihydrocapsaicin

Capsaicin and Dihydrocapsaicin are the two main capsaicinoids found in chili peppers. Together, they account for about 80–90% of the total “heat”. Both act on the TRPV1 receptors in sensory nerves, triggering the burning sensation we associate with spicy food.

-

Capsaicin is usually the dominant compound, slightly stronger in heat intensity.

-

Dihydrocapsaicin has a similar burning effect but with a slightly different molecular structure (saturated bond in its side chain).

-

Both are hydrophobic, so they dissolve in fats/oils rather than water.

-

Their relative concentration varies by chili variety, but most hot peppers contain both.

Comparison Table: Capsaicin vs. Dihydrocapsaicin

| Feature | Capsaicin 🌶️ | Dihydrocapsaicin 🌶️ |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | C18H27NO3 | C18H29NO3 |

| Structure | Contains a double bond in side chain (unsaturated) | No double bond in side chain (saturated) |

| Relative Abundance | ~60–70% of total capsaicinoids | ~20–30% of total capsaicinoids |

| Heat Contribution | Slightly higher pungency | Similar pungency, sometimes described as smoother |

| Scoville Rating | ~16 million SHU (pure form) | ~16 million SHU (pure form) |

| Polarity | Hydrophobic (dissolves in fats, oils, alcohol) | Hydrophobic (same solubility) |

| Biological Effect | Activates TRPV1 receptors → burning, heat, endorphin release | Activates TRPV1 receptors similarly |

| Therapeutic Use | Topical pain relief creams, research in metabolism | Same, often studied in combination with capsaicin |

Key Takeaway:

Both compounds are almost equal in heat intensity, but differ in molecular structure and proportion in peppers. Capsaicin is usually dominant, while dihydrocapsaicin plays a supporting role.

more Fascinating Facts about Capsaicin

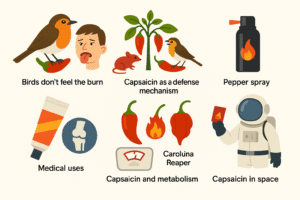

-

Birds Don’t Feel the Burn

Birds lack the TRPV1 receptor sensitivity to capsaicin, so they can eat the hottest chilies without discomfort. This helps spread chili seeds over long distances in nature. -

Capsaicin as a Defense Mechanism

Plants in the Capsicum genus evolved capsaicin to deter mammals (which destroy seeds by chewing) but not birds (which spread seeds intact). -

Medical Uses

Capsaicin is used in topical pain relief creams (for arthritis, nerve pain, shingles) because repeated application causes desensitization of pain nerves. -

Capsaicin and Metabolism

It can slightly increase metabolic rate and promote fat oxidation, which is why it’s sometimes marketed in weight-loss supplements. -

Pepper Spray

Pure capsaicin and related capsaicinoids are the active ingredients in pepper spray, used for self-defense and crowd control. -

World’s Hottest Peppers

The Carolina Reaper and other super-hot varieties (like Ghost Pepper, Trinidad Moruga Scorpion) have such high capsaicin levels that they can cause temporary numbness, dizziness, or hiccups. -

Capsaicin in Space

Astronauts have reported that food tastes bland in microgravity. Hot sauce and chili-based foods (rich in capsaicin) are popular on the ISS because the burn sensation bypasses “taste fatigue.”